|

|

Vandalism or Revitalization? Koolhaas Reworks Mies’ Masterpiece

Mona Jahedi

Iran, November 2004

The IIT campus is acknowledged as the birthplace of post-war modern American architecture. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the person responsible for the development of the IIT campus refined the grammar of modern architectural language and “perfected its ideas, structures, proportions, and geometry” (IIT Magazine 7).

In 1938 Mies fled Germany, where the Nazis had shut down the Bauhaus, and became the head of IIT’s architecture program shortly after his arrival in Chicago. Soon he was asked to design the institute’s new campus; a plan, which was to become the milestone for future developments. His master plan provided a basic grid where he placed twenty of his structures. Nevertheless, after his departure the campus remained untouched for several years.

In 1998, IIT hosted a competition for the design of the McCormick Tribune Campus Center. Koolhaas’ design, which won the competition, provoked much controversy. Koolhaas’ design despite being very different from Mies’ master plan responds to time and place and gives a new context to the IIT campus, whose density has dropped over time.

****

According to IIT’s dean of architecture, Donna Robertson, the original site chosen for the IIT campus was east of State Street, which was “full of tenement housing” (Becker 5). Mies had been given “the architect's dream, the tabula rasa, the blank slate, wiped clean of all the contaminations of the past” (Becker 5). He produced a vision for the Illinois Institute of Technology’s campus through a comprehensive master plan between 1938 and 1941. Illustrated through a set of drawings, he organized the space between and within buildings around a 24-foot grid.

This grid provided a spatial module for building projects of the future. It also gave rhythm and coherence to the campus. Mies also designed interior spaces with the same flexibility to alteration for the purpose of accommodating future needs. His spaces tend to slide from interior to exterior through a simple palette of steel, glass and brick. The minimalist form of his buildings combined with free-flowing spaces created an international sensation and suggested a new architectural vocabulary known later as the International Style.

He explored the style in his twenty buildings, which converted the IIT to the greatest collection of Miesian structures in the world. However, he left the rest of the campus to future designers with the potentiality of filling and extending his grid.

Despite this the campus remained untouched for many years after his last building was built in 1956. Over the next decade, renovations took place on some of his structures where needed. However, very few new structures were added to the campus since his original campus design was believed to allow “for renovation rather than replacements” (Lubell 39). The idea of not destroying masterpieces went as far as opposing any development that even touched Mies’s buildings in any way. These Mies defenders ignored the fact that however fabulous Mies’ buildings were at the time that were built, they might have lost some of their vibrancy after 50 years.

They also ignored Mies’ belief in adaptability. Mies took into consideration the inevitable changes in society, culture and technology. He believed a good design to be adaptable to these changes; therefore, his structures were designed to adapt and change over time. The future designers appeared to be very cautious of altering the master’s buildings or his overall vision for the campus. Few new buildings were built and all these additions remained very truthful to his idiom. After his death in 1969, construction stopped and also the area around the school declined dramatically, causing a drop in school’s enrolment.

****

In the fall of 1997, the Illinois Institute of Technology in an attempt to bring back their school’s popularity, invited designers to attend a competition for the design of a new campus center for students. The announcement started a “mixture of anticipation and skepticism” among the faculty, the students and the designers (Vinci 104). For those who were far removed from the time when Mies was the director of the school of architecture, the change was exciting and provoking. However, the older generation of the faculty, who were still religiously teaching Mies’ principles, became very skeptical towards change.

The idea of change to them was daunting; it was considered a crime against Mies’ theory. They believed that the new campus center should be a building like any other Mies’ buildings. However, the competition opened a wide range of possibilities: from structures that were almost identical to Mies’s buildings to ones sitting on the opposite pole of his style. Five finalists were picked from 39 architects who responded to the invitation. Surprisingly “the jury rejected Eisenman’s subterranean plan, Hadid’s futurist design, Jahn’s rational design, and Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa’s austere minimalist pavilion in favor of Koolhaas’ proposal” (Vinci 107). Ironically, Koolhaas’ design was the furthest in style from the Mies’ theory, and was going to alter one of his most famous buildings on the campus: the Commons Building.

****

Koolhaas was chosen over Chicago’s own Helmut Jahn who followed Miesian style more than any other participant. Jahn, however, was commissioned to design a row of dormitories, labeled State Street Village, that were joined to the Tribune Center later in 2003. Koolhaas and Jahn’s structures are very different in form and function and also in their relation to Miesian architecture. The dormitories are organized simply and methodically, focusing on a single goal while Koolhaas’ Tribune Center provides a wide range of spaces serving variety of activities. He has decided to create new “hybrid activities” by putting the different elements such as sport bar, bookstore, post office, and café rubbing against each other. He doesn’t try to control or separate functions, but instead he attempts to bring them together creating a chaotic hub of activities.

On the other hand, Jahn’s choice of material does not go beyond Mies’ palette. Jahn’s attention to proportion and details is praised by Mies followers. He has also attracted many positive opinions of his dormitory by making it effective in time-span and budget. The State Street Village came in “under budget at $18.7 million” versus Tribune Center that was over budget at about $23 million and was both begun before and finished after the campus center (Schulz 37). Given Mies’ place in IIT history, it would have been impossible for Jahn and Koolhaas to pursue their designs without being aware of his memory. However each paid their homage to the master in completely different manners. Jahn, himself a student of IIT, follows the well known expressive use of steel and glass that is evident in Mies’ buildings. Jahn’s design pays homage to Mies in a very clear and direct way: his dormitories stand comfortably across from Mies’ Crown Hall without changing the context of it as Koolhaas does towards the Common Building.

****

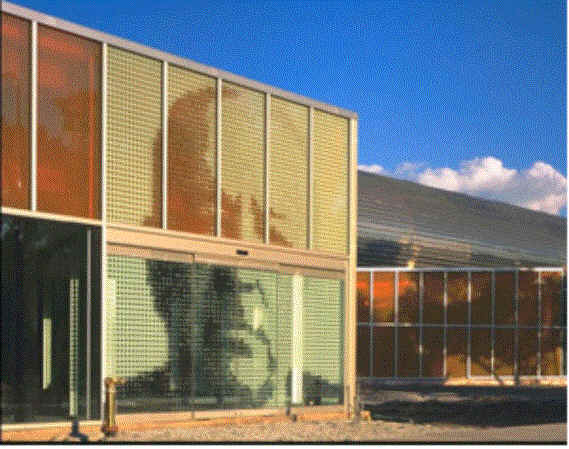

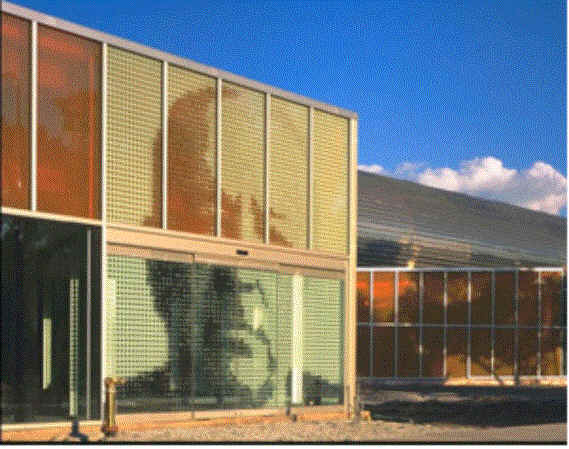

One of the controversies behind Koolhaas’ design is the outcry for saving the Commons Building. The Commons Building is a freestanding structure of glass, steel and brick that was designed by Mies in 1951. The building is described by many to be a “hallmark of Mies’ work which has enlightened generations of architects” (Vinci 108). It is as clear and simple as any of his other buildings at IIT, with its exposed steel structure and glass and brick infill panels. The Koolhaas’ plan however asked for some remodeling of the Commons Building. Koolhaas proposed to annex his new structure to the Commons building in hope of revitalizing the old structure. The Tribune Center was to touch the Commons Building in two of its elevations and required an alteration of the Commons building in order to adopt the new use: dining facilities. According to Vinci, “to this date… no successive architect has considered annexing or altering any of Mies’ original architecture” (Koolhaas 189). The idea of change once again became the issue.

The defenders of Mies tried to stop Koolhaas, saying that his ignorance towards the old structure will make the Commons Building suffer. But the fact is that the Commons Building has been altered several times before without significant opposition. The interior has undergone so many changes that it has become unrecognizable. If the opponents of Koolhaas’ design are against any changes to the building and are very tough on preserving the Commons Building, why did they allow for the previous alterations?

These defenders in their attempt to keep Mies’ architecture untouched can make them suffer even more. Leaving the old structure, whose form and function have not changed through time and as fast as the world of technology has, is a crime against it. The pressure of preservation can lead to emptying the structure from life when some minor alteration can give life to it. The modification in this project should not be considered as vandalism but a revitalization of the Commons Building. It should be recognized that although the Commons Building exemplified the highest modernism, the effects are different fifty years after it was built.

****

Koolhaas believes that Mies’ IIT is marooned since the surrounding city life has lost its vibrancy, which has “turned the campus into a metaphorical tabula rasa surrounded by a real tabula rasa” (Koolhaas 182). The Commons Building too is a “no-man’s land” which is marooned from the city. Although its symmetry and balance is contrasted with the Koolhaas’ revolutionary design, it has been given a context it had lost long ago.

Rem Koolhaas, despite the opinion of many believing that he does not respect Mies, pays respect to him but in a very indirect way, unlike Helmut Jahn. He cares for Mies’ structure not by duplicating it, but by changing its structure to fit into the 21st century. Koolhaas is actually very interested in Mies and his architecture; he finds Mies the opposite and thus more attractive. He has studied, excavated and reassembled Mies and has also confessed that he does “not respect Mies, [he] loves Mies” (Koolhaas 182).

****

Studying Mies, Koolhaas has rediscovered many architectural concepts, such as color. Koolhaas is fascinated with the implications of color, which might not be readily apparent in some of Mies’ works. Their different use of color is evident in these two buildings, which contrast with and complement each other. Koolhaas’ choice of color in the Tribune Center is very unusual and unique and might contrast with the subtle exterior of Commons Building, but it raises the issue of color in a broader sense. Bringing up the issue of color, one pays more attention to the color in Mies’ Commons Building, which otherwise can be interpreted as a colorless structure. Other than the effect that this bright color has on the old adjacent structure, it plays an important role in the image of the new structure. The color becomes a keynote in Koolhaas’ design, giving a sense of unity to the structure. The orange color of the raised tube, complemented with transparently orange walls and aggressively uneven vertical stripes, contributes to the overall theme of his design.

Other than giving the structure a unique identity, the bright orange and tomato red colors also contribute to the visual interest of the campus as a whole. It grabs attention and stay in the memory of the visitor. According to Koolhaas, potential students and their parents decide whether to enroll in an average of five seconds (Koolhaas 190). Therefore, leaving a good impression is crucial for the university, especially when the enrolment has dropped dramatically.

Tribune

The Tribune Center’s impression, whether because of its strange form or the rare color, might be a reason that the enrolment has increased recently and that the university is winning back its high quality students and regaining its popularity.

****

Although Koolhaas’s design has created a great contrast with orderly rhythm and symmetry of Mies’ design, it has deviated from Mies in other respects. Looking at Koolhaas and Mies more in depth, it becomes evident that “both men acknowledge a state of modern urban disorder and confusion” (Schulz). The difference in their style comes from the way that each treats this disorder and confusion. Mies converts the chaos into order through a set of “rational alternatives” that results in a modern-logical linear architecture. Mies believes in architecture as a set of orders where each part is created following a reason. Koolhaas, on the other hand, decides to “accept the world in all its sloppiness and somehow make that into a culture” (Hume 14).

Koolhaas’ design is all about movement with its “shifting planes, slanting surfaces, changing colors, and the celebration of complexity” (Hume 14).

The Tribune Center is as much about movement and complexity as Mies’ structures are about simplicity, such as the Crown Hall with its glass-walls and column-free interior. Koolhaas rejects Mies’ rules of simplicity and challenges Mies’ desire for purity and clarity. Koolhaas believes that it takes more complexity for a design to become successful and efficient in contemporary society. That is why his design responds to technological changes, trying to keep the new generation of students satisfied. Emphasizing the importance of the students, he designs a student center that can be responded to and enjoyed by the students. He understands that the new generation of students is capable of understanding complexity whether it is in the space, or the material or the overall design.

Therefore, he has packed variety of levels, ceiling heights and materials into a single story, encouraging one to respond to multiple layers of information in a fast and casual way. However, the space he has created might not be familiar to someone who has been following the rules of Mies and others, and is used to the plain spaces. Robert Venturi approves of his “spatial maneuvers” and agrees with him in the concept of architecture of today has been “too slow”, when it should be grounded in a “casual and fast spirit” (Stephens 3). According to Venturi “space is no longer the essential architectural element of our time” (Stephens 3).

*****

Despite what many of Mies’ followers believe, Koolhaas has paid homage to Mies in many different ways, some of which are as evident as the six meter tall portrait of him on the front door, and some are hidden through his building. Some of the elements that he has used in his design can be attributed to Mies: for example the use of exposed I-beam. Mies used I-beams on the Minerals and Metals Research building for the first time. He used them on the long walls as they were hidden behind a curtain wall of glass and brick, and on the shorter walls he used them in an exposed way. These exposed I-beams became a signature element in much of Mies’ later work.

There are other components in Koolhaas’ building that reference IIT’s master architect: “the Mies Bridge, an elevated shortcut that features an up-close view of Mies’ Commons Building; an outdoor courtyard space that allows an intimate view of the Commons; and a suite of conference rooms that follow the color palette-blue, yellow and brown- of Mies’ long time collaborator, Lily Reich” (IIT Magazine 9).

*****

The McCormick Tribune Campus Center becomes the focus of the ongoing debate about the validity of Mies's ideas and the direction of modern architecture. Similar to any revolutionary idea, it provokes great controversy. Koolhaas’ daring concept is as revolutionary in today’s society as Mies modernism was fifty years ago. Koolhaas’ architecture represents a dramatic force that is shaping the direction of architecture for the next century, stemming from the principles previously established by Mies van der Rohe. and other modernists.

He “pushes the envelope on architectural design for new generation” (IIT Magazin 7). His design, innovative and groundbreaking, gives a new context to the IIT campus as well as to Mies’ style. His design, however different from Mies’ vision for IIT, introduces the past and the present of IIT. It is undeniable that the new student center is the bustling hub of student life on campus and has revitalized the campus as well as Mies’ Commons Building.

Works Cited

Becker, Lynn. “Oedipus Rem.” Repeat: observation on architecture. Architecture. 26 September 2003: 5. .

Hume, Christopher. “Of Mies and Rem.” The Toronto Star (May 2004): 14

Koolhaas, Rem. Content. Koln, Germany: Taschen Publishing, 2004

Lubell, Sam. “IIT Campus transforming thanks to new additions.” Architectural Records 191.9 (September 2003): 39

Mertins, Detlef. “Design after Mies [Illinois Institute of Technology, McCormick Tribune Campus Center]” Any 24 (1999): 14-19

“Mies van der Rohe and the creation of a New Architecture on the IIT campus”, Chicago Reader. 26 September 2003, .

Pierce, Kevin. “IIT at a crossroads: a new student center for Mies' campus.” Competitions 8.2 (Summer 1998): 4-23

Russell, James. “Architecture Without Artistry.” Architectural Record 192.7 (July 2004): 98

Schulze, Franz. “Less or More Miesian?” Art in America 92.1 (January 2004): 36-39

Stephens, Suzanne. “Iconoclasm invades iconic territory with Rem Koolhaas’s design for the new IIT Campus Center in Chicago.” Architectural Record 192.5 (May 2004): 3.

Vinci, John. “Mies’ IIT Commons Building and Rem Koolhaas.” The Structurist 41.42 (2001-2002): 104-108

“IIT beyond Mies: a new urban focus, Chicago, Illinois.” Praxis: journal of writing and building 1.0 (Fall 1999): 14-21

“Project for the IIT student center competition, Chicago, Illinois, USA 2001.” A & U: architecture and urbanism 3.342 (March 1999): 52-61

“Success from the Ground Up.” IIT Magazine (Winter 2004): 2-9

Westrope, Jason. “Wrestling with the Zeitgeist; if architecture is frozen music, then Rem Koolhaas is the architect for the post-Napster generation.” Architecture Review (October 2004),

|

|